Asian Arts Council 2024-25 - FY25 - General Meeting Lectures

Each month the Asian Arts Council presents a program featuring a distinguished scholar, curator, collector or Asian arts enthusiast of note. We meet the last Thursday of the month on Zoom, and sometimes in person. Members and Docents are sent a link every month as part of membership. We welcome new members! Non-members may register by finding the date on the calendar of The San Diego Museum of Art. Click here! Once registered, an invitation email will be sent. Donations are welcome to help bring speakers.

Because descriptions for the last few lectures of FY24 are quickly archived, this year April through June are kept for easy reference through September. After that, check the archives page.

Click on a date line below for a lecture summary from the Asian Arts Council Newsletter.

July 25 - 1:00 p.m. True View Landscape Painting of the Joseon Dynasty Almiede "Allie" Arnell, JD, Docent, San Diego Museum of Art, in charge of Virtual Tours, Art History Instructor, past co-Chair AAC Study Group

The innovations in landscape painting that occurred during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) of Korea were explored by Allie Arnell, SDMA Docent, in True View Landscape Painting of the Joseon Dynasty. Prior to the Joseon period, Chinese culture and art were embraced by Korea, resulting in depictions of Chinese mountains in the landscape paintings of that time. With the advent of the Joseon, Korea’s interest grew in its own history and sacred places, especially the Diamond Mountains. Jeong Seon (1676-1759), known as the “father of true view” painting, repeatedly traveled to the Diamond Mountains to paint their riveting views of spiked peaks, plunging waterfalls and the boulder-strewn landscape, capturing not just their likeness, but their essence and the feeling of being a part of such compelling mountainscapes. His innovative style contrasted light and dark areas of the mountains, a birdseye panoramic viewpoint, and employed a series of vertical strokes to represent the vertical peaks and ink dots or short horizontal strokes to depict trees and plants. Later artists were influenced by his style and his ability to engender the longing to be in the presence of these mountains’ grandeur.

Aug 29 - 1:00 p.m. Treasured & Quotidian Objects: Still Lifes in Chinese Art Heather Simmerman, Ph.D., San Diego Museum of Art docent, AAC Vice Chair and Study Group co-chair, and writer of the Asian Collection Insights column

Early renditions of still life in China are found in Chan (Zen) Buddhist paintings from the Song period, which were used for meditation to gain intuitive insight “outside the scriptures.” Though flower paintings also originated with Buddhist art as representations of offerings, over the centuries flowers and plants acquired a rich range of associated meanings, largely from poetry, so scholar-painters (i.e. the literati) from the Song period and onward began to systematically exploit these possibilities for conveying meaning through their pictures. To satisfy growing demand from the prosperous middle class, urban studio masters in the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) updated and popularized the qinggong, 清供,”elegant offering” style of auspicious flowers and plants with added antiquities and scholar’s studio items in affordable prints for New Year wishes and other seasonal or personal well-wishes and gifts.

Scholars appreciating antiquities were a popular painting theme during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties, and featured displays of bronze antiquities, scholar’s rocks and studio implements, and other collectibles. Depictions of the objects became the sole focus of artistic renderings in various media with the “hundred antiques” pattern: porcelains, mixed media cloisonné and jade carvings on wood panel, a silk table valance, rugs, enameled teapots, opium boxes, and snuff bottles.

Naturalistic ink and color paintings of flowers, plants, and rocks were created as far back as the Song dynasty in a style called xiesheng 寫生, or “painting from life.” Western techniques of three dimensional perspective and shading were introduced by Jesuit priests acting as imperial court painters in the late Ming – early Qing period. From the late Qing period, artists in China have embraced the still life motif, combining traditional Chinese stylistic elements such as the daxieyi freehand expressive brushwork with modern more vibrant colors and a focus on egalitarian rather than elitist objects.

Heather Simmerman earned a Ph.D. in chemistry from Indiana University, then pursued a career in the biotech industry. In addition to being a Museum docent, and AAC Vice Chair, she has been accepted into the University of London SOAS-Alphawood program of study for the Postgraduate Certificate in Asian Art commencing Fall 2024.

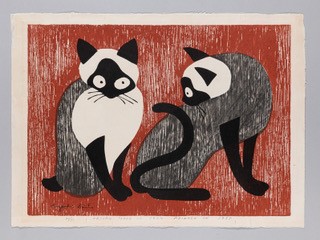

Sep. 26 - 1:00 p.m. Devine Felines in Japanese Art Riannon Paget, Curator of Asian art, Center for Asian Art, John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art

Rhiannon Paget is Curator of Asian Art at The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Florida State University, in Sarasota, Florida. A specialist of Japanese art, she has published research on paintings, textiles, popular visual culture, and especially of Art, Florida State University, in Sarasota, Florida. A specialist of Japanese art, she has published research on paintings, textiles, popular visual culture, and especially woodblock prints, most recently Divine Felines: The Cat in Japanese Art (2023). She has curated numerous exhibitions, including Mountains of the Mind: Scholars’ Rocks in China and Beyond (2023–24), and Saitō Kiyoshi: Graphic Awakening (2021). She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Sydney, Australia.

Oct. 31 - 1:00 p.m. Blue Gold, Indigo - IN PERSON at the Mingei International Museum Emily Hanna, Director of Exhibitions and Chief Curator, Mingei International Museum

Dr. Emily Hanna is Director of Exhibitions and Chief Curator at Mingei International Museum. She began her curatorial career at the Metropolitan Museum of Art where she received a doctoral fellowship and wrote her dissertation on African masquerade. She received a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa, with areas of specialty in African, Pre-Columbian, and Native American art. She has curated over 40 exhibitions at institutions including the High Museum of Art, and the Birmingham Museum of Art, where she served as Senior Curator and Department Head. She also taught art history at the university level for 12 years. Emily is co-curator of the exhibition Blue Gold: The Art and Science of Indigo.

Nov & Dec

No Meetings

Enjoy the holidays!

Jan. 30, 2025 - 1:00 p.m.

KIMONO: Garment, Canvas, and Artistic Muse

Meher McArthur

Moved by a visit to Manzanar, where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during WWII, Peter Liashkov fashioned a monumental-scale kimono from thin polypropylene fabric, acrylic and ashes printed with images of living conditions, rusted cots and a looming guard tower on the back to express the loss and suffering of its inhabitants.

Feb 27 - 1:00 p.m.

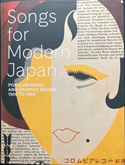

Visualizing Music in Modern Japan: Sheet Music (and Music Ephemera) at the Crossroads of Modern Mass Culture

Kendall Brown, Ph.D.

In the 1920s, sheet music for the harmonica was popular, and school children were taught to read music and play the instrument. The artwork on the covers of sheet music ranged from art deco, to realism and abstract, and captured the changing trends of modern culture in their illustrations. Mass marketing developed to sell not only sheet music, but also the records and movies that featured those songs. During the period of rising militarism and war in the 1930s and 1940s, sheet music covers appealed to the country’s patriotism by depicting war planes and uniformed soldiers.

Kendall Brown is emeritus Professor of Asian Art History in the Art Department at California State University Long Beach. He is an art historian and has published and curated widely on Japanese art and Japanese-style gardens in North America. In 2024, for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston he guest curated the exhibition, Songs for Modern Japan: The Art of Japanese Sheet Music, 1905- 1950.

Mar 27 - 1:00 p.m.

Transcendent Clay: The Kondō Family’s Path of Porcelain Innovations

Andreas Marks

A summary of this lecture will be posted here the month after the lecture is given.

Apr 24 - 1:00 p.m.

Encountering Iban Textiles from Borneo

Thomas Murray and Kristal Hale

A summary of this lecture will be posted here a month or two after the lecture is given.

May 29 - 1:00 p.m.

How the Silk Road was Opened

Lily Birmingham, Docent, San Diego Museum of Art

A summary of this lecture will be posted here the month after the lecture is given.

Jun 26 - 1:00 p.m.

Lecture and Officer Installation

Allie Arnell

A summary of this lecture will be posted here the month after the lecture is given.